A version of the club drug is expected to be approved for depression in March. Researchers think it could help treat suicidal thinking.

Joe Wright has no doubt that ketamine saved his life. A 34-year-old high school teacher who writes poetry every day on a typewriter, Wright was plagued by suicidal impulses for years. The thoughts started coming on when he was a high schooler himself, on Staten Island, N.Y., and intensified during his first year of college. “It was an internal monologue, emphatic on how pointless it is to exist,” he says. “It’s like being ambushed by your own brain.”

He first tried to kill himself by swallowing a bottle of sleeping pills the summer after his sophomore year. Years of treatment with Prozac, Zoloft, Wellbutrin, and other antidepressants followed, but the desire for an end was never fully resolved. He started cutting himself on his arms and legs with a pencil-sharpener blade. Sometimes he’d burn himself with cigarettes. He remembers few details about his second and third suicide attempts. They were halfhearted; he drank himself into a stupor and once added Xanax into the mix.

Wright decided to try again in 2016, this time using a cocktail of drugs he’d ground into a powder. As he tells the story now, he was preparing to mix the powder into water and drink it when his dog jumped onto his lap. Suddenly he had a moment of clarity that shocked him into action. He started doing research and came upon a Columbia University study of a pharmaceutical treatment for severe depression and suicidality. It involved an infusion of ketamine, a decades-old anesthetic that’s also an infamous party drug. He immediately volunteered.

His first—and only—ketamine infusion made him feel dreamlike, goofy, and euphoric. He almost immediately started feeling more hopeful about life. He was more receptive to therapy. Less than a year later, he married. Today he says his dark moods are remote and manageable. Suicidal thoughts are largely gone. “If they had told me how much it would affect me, I wouldn’t have believed it,” Wright says. “It is unconscionable that it is not already approved for suicidal patients.”

The reasons it isn’t aren’t strictly medical. Over the past three decades, pharmaceutical companies have conducted hundreds of trials for at least 10 antidepressants to treat severe PMS, social anxiety disorder, and any number of conditions. What they’ve almost never done is test their drugs on the sickest people, those on the verge of suicide. There are ethical considerations: Doctors don’t want to give a placebo to a person who’s about to kill himself. And reputational concerns: A suicide in a drug trial could hurt a medication’s sales prospects.

The risk-benefit calculation has changed amid the suicide epidemic in the U.S. From 1999 to 2016, the rate of suicides increased by 30 percent. It’s now the second-leading cause of death for 10- to 34-year-olds, behind accidents. (Globally the opposite is true: Suicide is decreasing.) Growing economic disparity, returning veterans traumatized by war, the opioid crisis, easy access to guns—these have all been cited as reasons for the rise in America. There’s been no breakthrough in easing any of these circumstances.

But there is, finally, a serious quest for a suicide cure. Ketamine is at the center, and crucially the pharmaceutical industry now sees a path. The first ketamine-based drug, from Johnson & Johnson, could be approved for treatment-resistant depression by March and suicidal thinking within two years. Allergan Plc is not far behind in developing its own fast-acting antidepressant that could help suicidal patients. How this happened is one of the most hopeful tales of scientific research in recent memory.

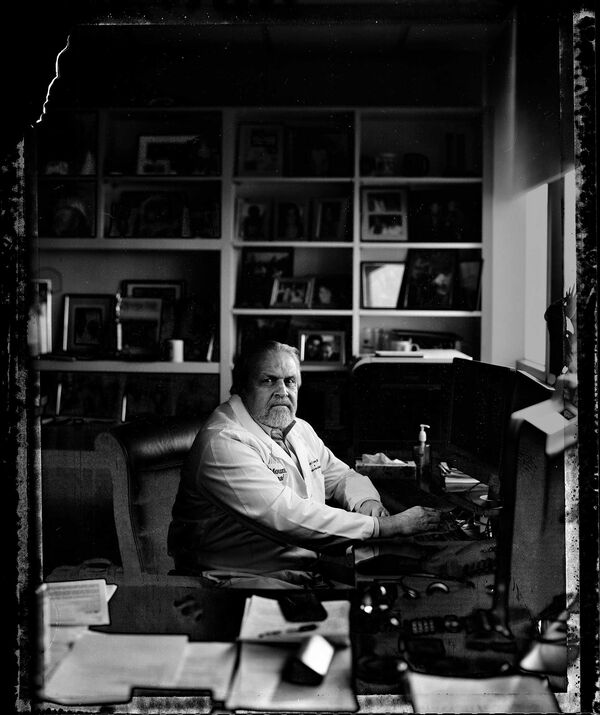

Dennis Charney, dean of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, works from an office filled with family pictures, diplomas, and awards from a long career in research. One thing on the wall is different from the rest: a patent for the use of a nasal-spray form of ketamine as a treatment for suicidal patients. The story of the drug is in some ways the story of Charney’s career.

In the 1990s he was a psychiatry professor, mentoring then associate professor John Krystal at Yale and trying to figure out how a deficit of serotonin played into depression. Back then, depression research was all about serotonin. The 1987 approval of Prozac, the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI, ushered in an era of what people in the industry call me-too drug development, research that seeks to improve on existing medicines rather than exploring new approaches. Within this narrow range, pharmaceutical companies churned out blockbuster after blockbuster. One in eight Americans age 12 and older reported using antidepressants within the past month, according to a survey conducted from 2011 to 2014 by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Charney was a depression guy; Krystal was interested in schizophrenia. Their curiosity led them to the same place: the glutamate system, what Krystal calls the “main information highway of the higher brain.” (Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter, which helps brain cells communicate. It’s considered crucial in learning and memory formation.) They had already used ketamine to temporarily produce schizophrenia-like symptoms, to better understand glutamate’s role in that condition. In the mid-1990s they decided to conduct a single-dose study of ketamine on nine patients (two ultimately dropped out) at the Yale-affiliated VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven to see how depressed people would react to the drug.

“If we had done the typical thing … we would have completely missed the antidepressant effect”

Outside the field of anesthesiology, ketamine is known, if it’s known at all, for its abuse potential. Street users sometimes take doses large enough to enter what’s known as a “K hole,” a state in which they’re unable to interact with the world around them. Over the course of a day, those recreational doses can be as much as 100 times greater than the tiny amount Charney and Krystal were planning to give to patients. Nonetheless, they decided to monitor patients for 72 hours—well beyond the two hours that ketamine produces obvious behavioral effects—just to be careful not to miss any negative effects that might crop up. “If we had done the typical thing that we do with these drug tests,” Krystal says, “we would have completely missed the antidepressant effect of ketamine.”

Checking on patients four hours after the drug had been administered, the researchers saw something unexpected. “To our surprise,” Charney says, “the patients started saying they were better, they were better in a few hours.” This was unheard of. Antidepressants are known for taking weeks or months to work, and about a third of patients aren’t sufficiently helped by the drugs. “We were shocked,” says Krystal, who now chairs the Yale psychiatry department. “We didn’t submit the results for publication for several years.”

When Charney and Krystal did publish their findings, in 2000, they attracted almost no notice. Perhaps that was because the trial was so small and the results were almost too good to be true. Or maybe it was ketamine’s reputation as an illicit drug. Or the side effects, which have always been problematic: Ketamine can cause patients to disassociate, meaning they enter a state in which they feel as if their mind and body aren’t connected.

But probably none of these factors mattered as much as the bald economic reality. The pharmaceutical industry is not in the business of spending hundreds of millions of dollars to do large-scale studies of an old, cheap drug like ketamine. Originally developed as a safer alternative to the anesthetic phencyclidine, better known as PCP or angel dust, ketamine has been approved since 1970. There’s rarely profit in developing a medication that’s been off patent a long time, even if scientists find an entirely new use for it.

Somehow, even with all of this baggage, research into ketamine inched forward. The small study that almost wasn’t published has now been cited more than 2,000 times.

Suicide is described in medicine as resulting from a range of mental disorders and hardships—a tragedy with many possible roots. Conditions such as severe depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia are known risk factors. Childhood trauma or abuse may also be a contributor, and there may be genetic risk factors as well.

From these facts, John Mann, an Australian-born psychiatrist with a doctorate in neurochemistry, made a leap. If suicide has many causes, he hypothesized, then all suicidal brains might have certain characteristics in common. He’s since done some of the most high-profile work to illuminate what researchers call the biology of suicide. The phrase itself represents a bold idea—that there’s an underlying physiological susceptibility to suicide, apart from depression or another psychiatric disorder.

Mann moved to New York in 1978, and in 1982, at Cornell University, he started collecting the brains of people who’d killed themselves. He recruited Victoria Arango, now a leading expert in the field of suicide biology. The practice of studying postmortem brain tissue had largely fallen out of favor, and Mann wanted to reboot it. “He was very proud to take me to the freezer,” Arango says of the day Mann introduced her to the brain collection, which then numbered about 15. “I said, ‘What am I supposed to do with this?’ ”

They took the work, and the brains, first to the University of Pittsburgh, and then, in 1994, to Columbia. They’ve now amassed a collection of some 1,000 human brains—some from suicide victims, the others, control brains—filed neatly in freezers kept at –112F. The small Balkan country of Macedonia contributes the newest brains, thanks to a Columbia faculty member from there who helped arrange it. The Macedonian brains are frozen immediately after being removed and flown in trunks, chaperoned, some 4,700 miles to end up in shoe-box-size, QR-coded black boxes. Inside are dissected sections of pink tissue in plastic bags notated with markers: right side, left side, date of collection.

In the early 1990s, Mann and Arango discovered that depressed patients who killed themselves have subtle alterations in serotonin in certain regions of the brain. Mann remembers sitting with Arango and neurophysiologist Mark Underwood, her husband and longtime research partner, and analyzing the parts of the brain affected by the deficit. They struggled to make sense of it, until it dawned on them that these were the same brain regions described in a famous psychiatric case study. In 1848, Phineas Gage, an American railroad worker, was impaled through the skull by a 43-inch-long tamping iron when the explosives he was working with went off prematurely. He survived, but his personality was permanently altered. In a paper titled “Recovery From the Passage of an Iron Bar Through the Head,” his doctor wrote that Gage’s “animal propensities” had emerged and described him as using the “grossest profanity.” Modern research has shown that the tamping iron destroyed key areas of the brain involved in inhibition—the same areas that were altered in the depressed patients who’d committed suicide. For the group, this was a clue that the differences in the brain of suicidal patients were anatomically important.

“Most people inhibit suicide. They find a reason not to do it,” Underwood says. Thanks to subtle changes in the part of the brain that might normally control inhibition and top-down control, people who kill themselves “don’t find a reason not to do it,” he says.

About eight years ago, Mann saw ketamine research taking off in other corners of the scientific world and added the drug to his own work. In one trial, his group found that ketamine treatment could ease suicidal thoughts in 24 hours more effectively than a control drug. Crucially, they found that the antisuicidal effects of ketamine were to some extent independent of the antidepressant effect of the drug, which helped support their thesis that suicidal impulses aren’t necessarily just a byproduct of depression. It was this study, led by Michael Grunebaum, a colleague of Mann’s, that made a believer of Joe Wright.

“It’s like you have 50 pounds on your shoulders, and the ketamine takes 40 pounds off”

In 2000, the National Institutes of Health hired Charney to run both mood disorder and experimental drug research. It was the perfect place for him to forge ahead with ketamine. There he did the work to replicate what he and his colleagues at Yale had discovered. In a study published in 2006, led by researcher Carlos Zarate Jr., who now oversees NIH studies of ketamine and suicidality, an NIH team found that patients had “robust and rapid antidepressant effects” from a single dose of the drug within two hours. “We could not believe it. In the first few subjects we were like, ‘Oh, you can always find one patient or two who gets better,’ ” Zarate recalls.

In a 2009 study done at Mount Sinai, patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression showed rapid improvement in suicidal thinking within 24 hours. The next year, Zarate’s group demonstrated antisuicidal effects within 40 minutes. “That you could replicate the findings, the rapid findings, was quite eerie,” Zarate says.

Finally ketamine crossed back into commercial drug development. In 2009, Johnson & Johnson lured away Husseini Manji, a prominent NIH researcher who’d worked on the drug, to run its neuroscience division. J&J didn’t hire him explicitly to develop ketamine into a new pharmaceutical, but a few years into his tenure, Manji decided to look into it. This time it would come in a nasal-spray form of esketamine, a close chemical cousin. That would allow for patent protection. Further, the nasal spray removes some of the challenges that an IV form of the drug would present. Psychiatrists, for one thing, aren’t typically equipped to administer IV drugs in their offices.

While these wheels were slowly turning, some doctors—mostly psychiatrists and anesthesiologists—took action. Around 2012 they started opening ketamine clinics. Dozens have now popped up in major metropolitan areas. Insurance typically won’t touch it, but at these centers people can pay about $500 for an infusion of the drug. It was at one time a cultural phenomenon—a 2015 Bloomberg Businessweek story called it “the club drug cure.” Since then, the sense of novelty has dissipated. In September the American Society of Ketamine Physicians convened its first medical meeting about the unconventional use of the drug.

“You are literally saving lives,” Steven Mandel, an anesthesiologist-turned-ketamine provider, told a room of about 100 people, mostly doctors and nurse practitioners, who gathered in Austin to hear him and other early adopters talk about how they use the drug. Sporadic cheers interrupted the speakers as they presented anecdotes about its effectiveness.

There were also issues to address. A consensus statementin JAMA Psychiatry published in 2017 said there was an “urgent need for some guidance” on ketamine use. The authors were particularly concerned with the lack of data about the safety of prolonged use of the drug in people with mood disorders, citing “major gaps” in the medical community’s knowledge about its long-term impact.

The context for the off-label use of ketamine is a shrinking landscape for psychiatry treatment. An effort to deinstitutionalize the U.S. mental health system, which took hold in the 1960s, has almost resulted in the disappearance of psychiatric hospitals and even psychiatric beds within general hospitals. There were 37,679 psychiatric beds in state hospitals in 2016, down from 558,922 in 1955, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. Today a person is often discharged from a hospital within days of a suicide attempt, setting up a risky situation in which someone who may not have fully recovered ends up at home with a bunch of antidepressants that could take weeks to lift his mood, if they work at all.

A ketamine clinic can be the way out of this scenario—for people with access and means. For Dana Manning, a 53-year-old Maine resident who suffers from bipolar disorder, $500 is out of reach. “I want to die every day,” she says.

After trying to end her life in 2003 by overdosing on a cocktail of drugs including Xanax and Percocet, Manning tried virtually every drug approved for bipolar disorder. None stopped the mood swings. In 2010 the depression came back so intensely that she could barely get out of bed and had to quit her job as a medical records specialist. Electroconvulsive therapy, the last-ditch treatment for depressed patients who don’t respond to drugs, didn’t help.

Her psychiatrist went deep into the medical literature to find options and finally suggested ketamine. He was even able to get the state Medicaid program to cover it, she says. She received a total of four weekly infusions before she moved to Pennsylvania, where there were more family members nearby to care for her.

The first several weeks following her ketamine regimen were “the only time I can say I have felt normal” in 15 years, she says. “It’s like you have 50 pounds on your shoulders, and the ketamine takes 40 pounds off.”

She’s now back in Maine, and the depression has returned. Her current Medicare insurance won’t cover ketamine. She lives on $1,300 a month in disability income. “Knowing it is there and I can’t have it is beyond frustrating,” she says.

Ketamine is considered a “dirty” drug by scientists—it affects so many pathways and systems in the brain at the same time that it’s hard to single out the exact reason it works in the patients it does help. That’s one reason researchers continue to look for better versions of the drug. Another, of course, is that new versions are patentable. Should Johnson & Johnson’s esketamine hit the market, the ketamine pioneers and their research institutions stand to benefit. Yale’s Krystal, NIH’s Zarate, and Sinai’s Charney, all of whom are on the patent on Charney’s wall, will collect royalties based on the drug’s sales. J&J hasn’t said anything about potential pricing, but there’s every reason to believe the biggest breakthrough in depression treatment since Prozac will be expensive.

The company’s initial esketamine study in suicidal patients involved 68 people at high risk. To avoid concerns about using placebos on actively suicidal subjects, everyone received antidepressants and other standard treatments. About 40 percent of those who received esketamine were deemed no longer at risk of killing themselves within 24 hours. Two much larger trials are under way.

When Johnson & Johnson unveiled data from its esketamine study in treatment-resistant depression at the American Psychiatric Association meeting in May, the presentation was jammed. Esketamine could become the first-ever rapid-acting antidepressant, and physicians and investors are clamoring for any information about how it works. The results in suicidal patients should come later this year and could pave the way for a Food and Drug Administration filing for use in suicidal depressed patients in 2020. Allergan expects to have results from its suicide study next year, too.

“The truth is, what everybody cares about is, do they decrease suicide attempts?” says Gregory Simon, a psychiatrist and mental health researcher at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. “That is an incredibly important question that we hope to be able to answer, and we are planning for when these treatments become available.”

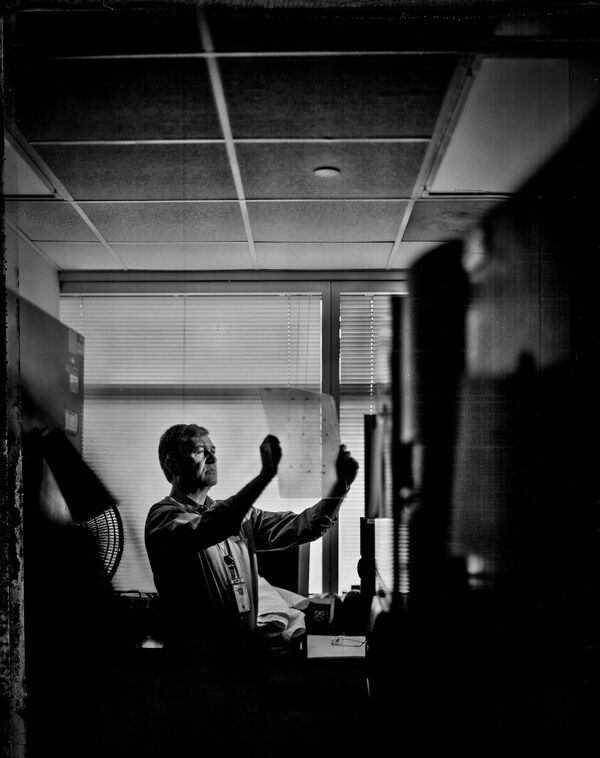

Exactly how ketamine and its cousin esketamine work is still the subject of intense debate. In essence, the drugs appear to provide a quick molecular reset button for brains impaired by stress or depression. Both ketamine and esketamine release a burst of glutamate. This, in turn, may trigger the growth of synapses, or neural connections, in brain areas that may play a role in mood and the ability to feel pleasure. It’s possible the drug works to prevent suicide by boosting those circuits while also reestablishing some of the inhibition needed to prevent a person from killing himself. “We certainly think that esketamine is working exactly on the circuitry of depression,” Manji says. “Are we homing in exactly on where suicidal ideation resides?” His former colleagues at NIH are trying to find that spot in the brain as well. Using polysomnography—sleep tests in which patients have nodes connected to various parts of their head to monitor brain activity—as well as MRIs and positron emission tomography, or PET scans, researchers can see how a patient’s brain responds to ketamine, to better understand exactly what it’s doing to quash suicidal thinking.

Concerns about the side effects of ketamine-style drugs linger. Some patients taking esketamine have reported experiencing disassociation symptoms. Johnson & Johnson calls the effects manageable and says they cropped up within an hour of the treatment, a period in which a person on the drug would likely be kept in the doctor’s office for monitoring. Some patients also experienced modest spikes in blood pressure within the same timeframe.

Nasal-spray dosing brings other issues. The Black Dog Institute in Australia and the University of New South Wales in Sydney, which teamed up to study a nasal-spray form of ketamine, published their findings last March in the Journal of Psychopharmacology. The researchers found that absorption rates were variable among patients. J&J says its own studies with esketamine contradict these findings.

But in the wake of the opioid crisis, perhaps the biggest worry is that loosening the reins too much on the use of ketamine and similar drugs could lead to a new abuse crisis. That’s why Wall Street analysts are particularly excited by Allergan’s rapid-acting antidepressant, rapastinel, which is about a year behind esketamine in testing. Researchers say it likely acts on the same target in the brain as ketamine, the NMDA receptor, but in a more subtle way that may avoid the disassociation side effects and abuse potential. Studies in lab animals show the drug doesn’t lead creatures to seek more of it, as they sometimes do with ketamine, says Allergan Vice President Armin Szegedi. Allergan’s medicine is an IV drug, but the company is developing an oral drug.

For its suicide study, Allergan is working hard to enroll veterans, one of the populations most affected by the recent spike in suicides, and has included several U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers as sites in the trial. More than 6,000 veterans died by suicide each year from 2008 to 2016, a rate that’s 50 percent higher than in the general population even after adjusting for demographics, according to VA data.

“How the brain mediates what makes us who we are is still a mystery, and maybe we will never fully understand it,” Szegedi says. “What really changed the landscape here is you had clinical data showing ‘This really does the trick.’ Once you find something in the darkness, you really have to figure out: Can you do something better, faster, safer?”